The following provides information with evidence and references on offshore wind farms in the UK that also help address some common myths:

- Wind Strength and the best locations for wind farms in the UK

- The Carbon Footprint of Wind Power in the UK

- Impact on Tourism

- Protection of Birds

- Relative benefits and cost of wind farms around the UK

- New alternative renewables

Wind Strength and the best locations for wind farms in the UK

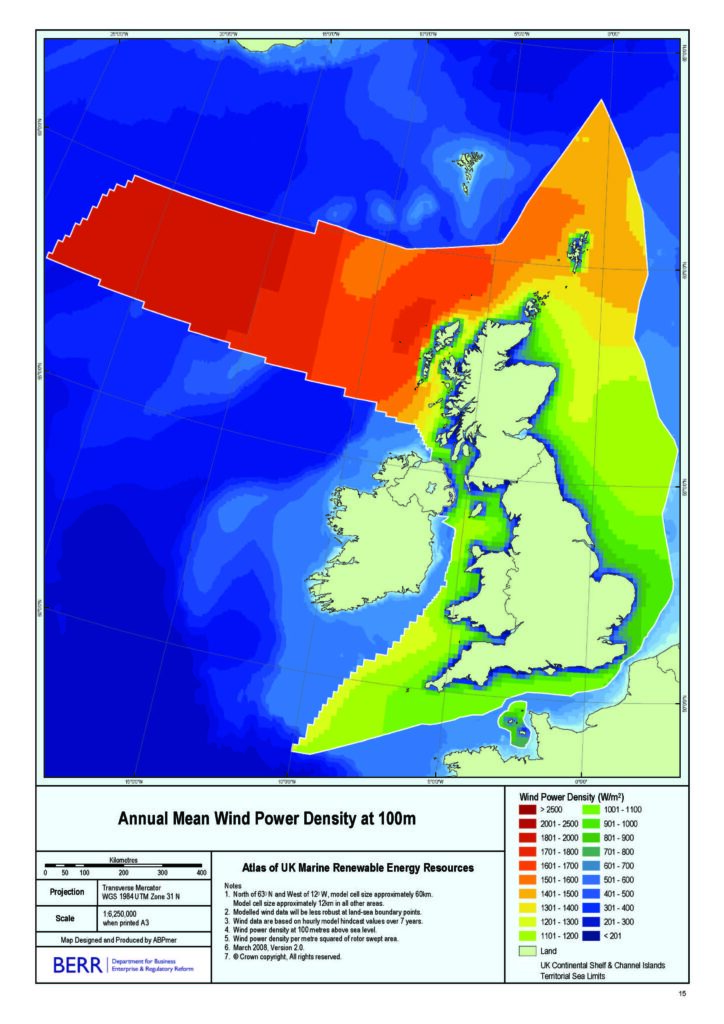

Wind farms provide an intermittent output. When the wind doesn’t blow no electricity is generated and the wind farm asset is wasted. In order to reach net-zero most effectively and quickly wind farms are best located where the wind strengths are higher and more constant. The best measure to determine the best locations for wind farms is the Wind Power Density (WPD). The map below shows that large areas of the North Sea and off the tip of Cornwall have areas in excess of 1000W/m2 whereas many of the areas close to the coast where, historically wind farms have been located have much lower wind power densities (200-300W/m2). The annual output (normally referred to as the capacity factor) for wind farms varies from 33% in areas of low wind to 60% in areas of high wind power.

Areas of the North Sea (Dogger Bank) are not too deep and fixed turbines can be used. In the areas of the Northern North Sea, off the tip of Cornwall, other parts of the Celtic Sea and off the North Coast of Scotland the wind strength is very high making them ideal for wind farms. However, these areas are in deep waters and require floating wind turbines. This technology is being developed and will be available in time to help reach the offshore wind target of 50GW by 2030. Currently planned wind farms are best located far offshore in relatively shallow areas with high wind power. These will be followed by wind farms even further offshore when floating technology takes over.

Each conventional wind turbine requires a significant quantity of rare earth minerals. These are in short supply globally and need to be used up carefully. This is a further reason for installing wind turbines only where they will be most efficient. For example, the GE Haliades X 13MW turbines use 7 tonnes of rare earth permanent magnets in their generator hub.

The Carbon Footprint of Wind Power in the UK

Wind Power is an excellent source of renewable energy. Offshore wind is much better then onshore wind as the wind power is significantly higher, normally the further offshore the better.

For wind power to properly support the transition to net-zero it must be supported by energy storage capable of storing the power it produces when its output is high (on windy days) so that on calm days when it produces no, or very little, output the grid can be fed by the stored energy. This combination of direct wind farm output and backup storage would then provide truly carbon free renewable energy. For a wind farm located in an area of high wind power density (i.e. Dogger Bank in the North Sea)with a nominal output of 1200MW and a 56% capacity factor the storage capacity would need to be 1035GWh. [This is based upon collecting the output from all the UK wind farms and storing the power when the total exceeds the annual average. The stored energy is feed back into the grid when the wind farm output is low to maintain constant output throughout the year.] The largest battery storage facility in the world has just become operational in Australia. It is the 300MW Tesla battery facility which could store 450MWh at an estimated capital cost of £150M. This single wind farm would need 2,300 of these which would have a capital cost of about £345B. When compared with a typical cost of the wind farm of £3B makes this completely uneconomic! Other technologies may be developed in the future like hydrogen storage in underground caverns but there are no current plans to develop such facilities and it is likely to be decades before we will have the capability to store the energy from even a single 1200MW wind farm.

In the meantime, the country will continue to depend upon liquid and natural gas power stations to provide electricity to the grid when there is not enough wind. The amount of gas-powered generation capacity required to support a wind farm depends upon the efficiency of the wind farm. Wind farms in areas of high wind power density which have a high capacity factor require less gas generation capacity than those in low wind power regions.

For example, a 1200MW wind farm close inshore with a capacity factor as low as 35% would require 6800 GWh of gas generation per year to fill in the periods on low wind and would produce 3.33 million tonnes of carbon emission per year. The equivalent wind farm in Dogger Bank (assuming a capacity factor of 56%) would only require 4600 GWh of gas generation and only produce 2.26 million tonnes of carbon emission per year – a saving of 1.08 million tonnes of carbon emission per year! (the calculation made using a static figure of 488g/kWh for a CCGT power station)

Impact of Wind Farms on Tourism

Studies show that impacts on tourism are negative but vary as to how negative depending on how important tourism is to the local economy and the nature of the tourist interest. While some argue that inshore windfarms will initially attract some people, the net impact is potentially negative, and this negative impact may change over the medium and longer terms in areas where the seascape is valued and intrinsic to socio-economic activities. Indications for areas where tourism plays a significant role in the local economy and employment are likely to see a reduction in annual tourism income of up to 20%[1]. This position may change with the public acceptance of the need for wind farms to tackle climate change.

[1] 20% is the reduction in tourism income projected by Bournemouth Borough Council in reference to the proposed Navitus Bay wind farm project (PINS reference EN010024).

Protection of Birds and other Wildlife

Locating Wind Farms further offshore minimizes the impact on our birds. The Government Report (OESEA2 NTS) states on page XIV: “Therefore, recognising that a large proportion of the bird sensitivities identified are concentrated in coastal waters, it is recommended that the bulk of new Offshore Wind Farms (OWF) generation capacity should be sited away from the coast, generally outside 12 nautical miles (some 22km).”

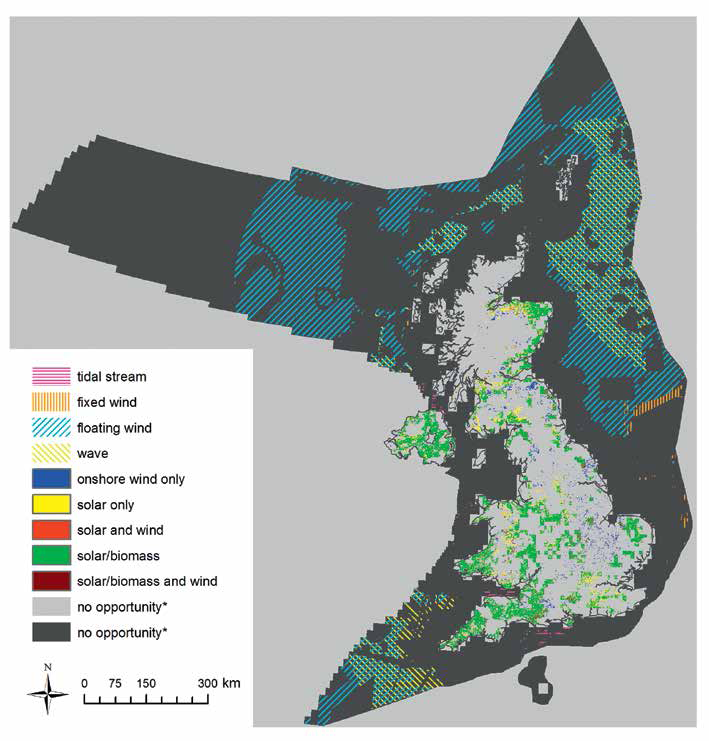

The RSPB published a report in 2016 “The RSPB’s 2050 Energy Vision” where it indicated its vision on where wind farms should be located to minimize the impact on birds. As can be seen from Figure 4 of that report there are no recommended areas close to shore. Far out in the North Sea is identified as having low impact on birds. The RSPB recognizes the benefit of floating wind farms and would ideally see all wind farms be floating and far offshore in deepest waters.

Pipistrelle bats and insects also migrate to the continental Europe from the South Coast of England and the East Coast to Belgium and the Netherlands. For their protection wind farms should not be in the areas shown in black. It also seems that Pipistrelle bats are attracted to wind turbines and are killed by them. Meaning that surveys of bats in an area before a wind farms is installed does not identify the full scale of the potential harm.

Offshore Transmission Network

The Government confirmed in the December 2020 Energy White paper that it supported the National Grid (ESO) proposal for an Offshore Transmission Network (OTN). This proposal is expected to save the country £6Bn by 2050 if fully implemented for the connection of offshore wind farms. The proposal is to create an offshore electricity transmission grid connecting the offshore wind farms together. This system will significantly increase the reliability of the connection of offshore wind farms to the grid by creating multiple connections as opposed to the current single radial connection from each wind farm to the onshore grid. The cost savings of new system comes from the big reduction of the number of onshore cable links. This new OTN would typically require only one onshore cable link for every three of four wind farms. To minimise cost to customers new wind farms should be located where they can connect to the OTN. These locations include the sea off North and East Scotland, Dogger Bank, Eastern Regions of the North Sea and, North Wales and Irish sea. Locating in other areas where the wind farms cannot connect to the OTN would be more expensive for customers.

New Alternative Renewables

The country should invest in new alternative renewables and not overstep the wind farm target with current technology:

7.98GW of extra capacity has been allocated by the Crown Estate (Round 4 Tender Stage 2). With this there is 59GW available to meet the national target of 40GW by 2030 according to the March 2021 project listing.

In January 2022 the Crown Estate Scotland announced a further 24.8GW resulting in a total of 83.8GW in the pipeline for 2030 to meet the increased target of 50GW announced in April 2022.

It is particularly important not to go beyond the target with the current, already dated technology. We should only accept Truly Green Wind Farms in the next 10 years. Driven by the urgent need to tackle climate change, and the need to reduce our dependence on gas the country needs to focus on renewable sources that are less intermittent than wind and solar. There are novel renewable energy technologies emerging all the time. It is important not install too much of the current intermittent technology too quickly only to find much better solutions emerging fast, which will require us to rebalance the power generation, making some of the existing wind power redundant. Alternative renewables which overcome intermittency and provide a constant source include:

- Fusion

- Small Modular Reactors

- Geothermal It is reported that one company, Quaise, expects to re-power the first fossil-fired plant in 2028.

- Wave and Tidal Energy – see the Ocean Race (these technologies are slightly intermittent – but would only require relatively small local storage capacity to make them constant sources.

Floating Offshore Wind

The Crown Estate now expects to deliver on the UK target of 1GW (i.e.1000MW) of floating offshore wind farms installed by 2030. This raised the 2021 pipeline to 60GW. These floating wind farms would be located far offshore in regions of very high wind power – resulting in less intermittency than current fixed wind farms. These wind farms would be far offshore in the Celtic Sea – way beyond the Cornish peninsular.

In the Crown Estate Scotland 2022 announcement it has allocated leases for more than 14GW of floating wind farms (and an extra 10GW of fixed wind farms) in high wind power areas off the north of Scotland. The recent Government energy strategy announced in April 2022 expects that at least 5GW of the 2030 target of 50GW offshore wind will be floating wind farms.